As coronavirus widens the renter-owner divide, housing policies will have to change

Much of the housing policy focus during the pandemic has rightly centred on the plight of people who are insecurely housed or homeless. Another strand of commentary has focused on a likely fall in property values.

But what does the pandemic mean for housing market inequalities in Australia? And what are the policy implications?

Read more:

Homelessness and overcrowding expose us all to coronavirus. Here’s what we can do to stop the spread

The renter-owner gap will widen

Despite concerns about house prices plummeting, the spread of COVID-19 is exposing a widening gap in housing markets between those who own zero housing wealth (renters) and those with substantial housing wealth (owners).

Australians with little to no housing wealth were already experiencing at least three key types of vulnerabilities before the pandemic in the form of work insecurity, financial stress and ill-health.

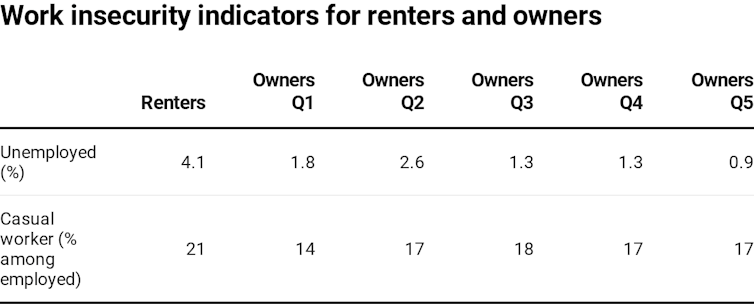

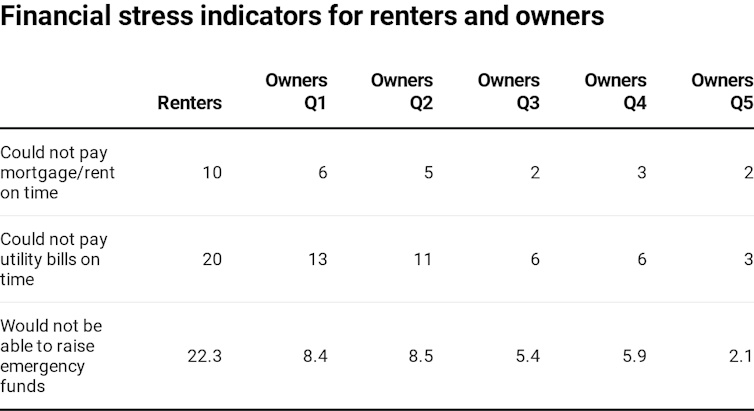

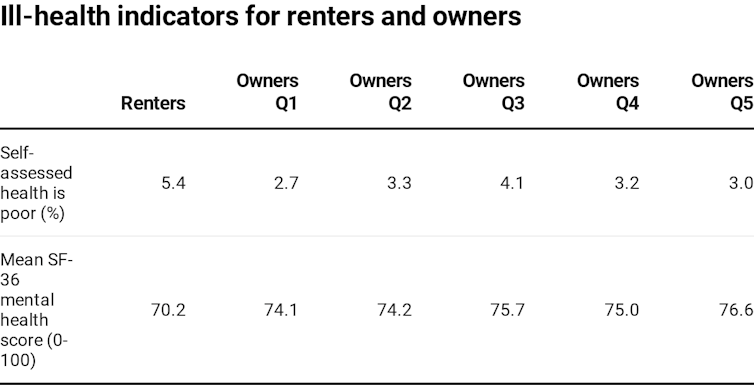

The charts below show the comparisons between renters and home owners in these three categories of vulnerability, using data from the HILDA Survey. Owners are ranked in quintiles by housing equity, from the bottom 20% (Q1) to the top 20% (Q5).

Renters were much more likely to be unemployed or in casual jobs than people with high housing wealth.

Author’s calculations from 2017 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics Survey data, Author provided

Both renters and owners with low housing equity were more likely to have difficulty paying their rent, mortgage and utility bills on time. They were less likely to be able to raise emergency funds when needed.

Author’s calculations from 2017 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics Survey data, Author provided

Read more:

Rents can and should be reduced or suspended for the coronavirus pandemic

Renters were also more likely to report poorer physical and mental health.

Author’s calculations from 2017 Household, Income and Labour Dynamics Survey data, Author provided

The spread of coronavirus has added to these existing vulnerabilities. Casual workers have been particularly vulnerable to job loss.

Read more:

Coronavirus puts casual workers at risk of homelessness unless they get more support

The social gradient in health is well-known. People on the bottom rungs of the socioeconomic ladder tend to be in poorer health. They are then more likely to develop serious health problems from the coronavirus.

Post-pandemic markets will add to inequalities

COVID-19 is making existing economic inequalities worse. And even in a post-pandemic world it can be expected to slow down wealth accumulation among renters.

Hysteresis is a term used to describe an economic event that persists into the future, after the factors that led to the event have disappeared. In labour markets, the long-term unemployed also suffer long-term damage to their job prospects as their skills deteriorate and they are regarded as less employable.

This hysteresis effect will likely spill over into housing markets. Any crisis-driven falls in house prices may be short-term as housing values remain relatively insulated by record low interest rates. People who are exposed to job loss, insecure work or ill-health during the crisis will face a greater struggle to regain their economic footing after the pandemic than those from more affluent backgrounds.

This means the wealth-accumulating capacity of people with little to no housing equity is further compromised during and after the pandemic. In short, renters could fall further behind in their ability to buy a home. The gap between the haves and have-nots will grow.

Read more:

Fall in ageing Australians’ home-ownership rates looms as seismic shock for housing policy

3 principles for post-pandemic policy

An even more unequal housing future for Australia is undesirable. The post-crisis housing debate will need to be conducted with three key elements in mind: equity, solidarity and security.

Equity in access to housing opportunities must not slide off policymakers’ radar. It is not a debatable fact that governments have long provided generous concessions for property buyers. These measures include capital gains tax discounts, family home exemptions from land tax and income support means tests, and negative gearing for investors.

These preferential tax treatments have far exceeded government spending on renters. Notwithstanding the benefits commonly associated with home ownership, restoring some balance in the distribution of subsidies between owners and renters is essential to narrow the widening chasm between them.

Solidarity between generations will be more crucial than ever before to preserve Australia’s social and economic fabric. The surge in national debt created in response to the crisis will likely be a multi-generational burden.

Some might be tempted to return to pitting the young against the old in housing debates. Policy thinking that encourages solidarity, rather than stoking tensions between generations, will be increasingly important. For instance, abolishing stamp duty together with levying land tax on all land will remove a key financial barrier to home purchases for both young first-time buyers and older downsizers.

The formation of the national cabinet to oversee the response to COVID-19 also provides a post-pandemic forum to forge federal-state cooperation on the required reforms. Federal support will be needed to help cover state revenue shortfalls in a gradual transition to land tax. On the other hand, the release of housing equity by older downsizers should ease pressures on the federal retirement incomes system.

Finally, it is time to reprioritise housing security as a foundation for fostering good health and economic participation. Critical public health measures to avoid the spread of disease, such as social distancing and staying at home, are inherently shelter-related. These measures are rarely achievable for people who are homeless or in overcrowded housing.![]()

Rachel Ong ViforJ, Professor of Economics, School of Economics, Finance and Property, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.