Ore-some: New date for Earth’s largest iron deposits offers clues for future exploration

Research led by Curtin University reveals that Earth’s largest iron ore deposits – in the Hamersley Province of Western Australia – are about one billion years younger than previously believed, a discovery which could greatly boost the search for more of the resource.

Using a new geochronology technique to accurately measure the age of iron oxide minerals, researchers found the Hamersley deposits formed between 1.4 and 1.1 billion years ago, rather than 2.2 billion years ago as previously estimated.

Lead author Dr Liam Courtney-Davies, who was a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Curtin University’s John de Laeter Centre at the time of the research and is now at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said the findings showed iron deposits formed during a period of major geological activity when ancient supercontinents were breaking apart and new ones were forming.

“The energy from this epic geological activity likely triggered the production of billions of tonnes of iron-rich rock across the Pilbara,” Dr Courtney-Davies said.

“The discovery of a link between these giant iron ore deposits and changes in supercontinent cycles enhances our understanding of ancient geological processes and improves our ability to predict where we should explore in the future.

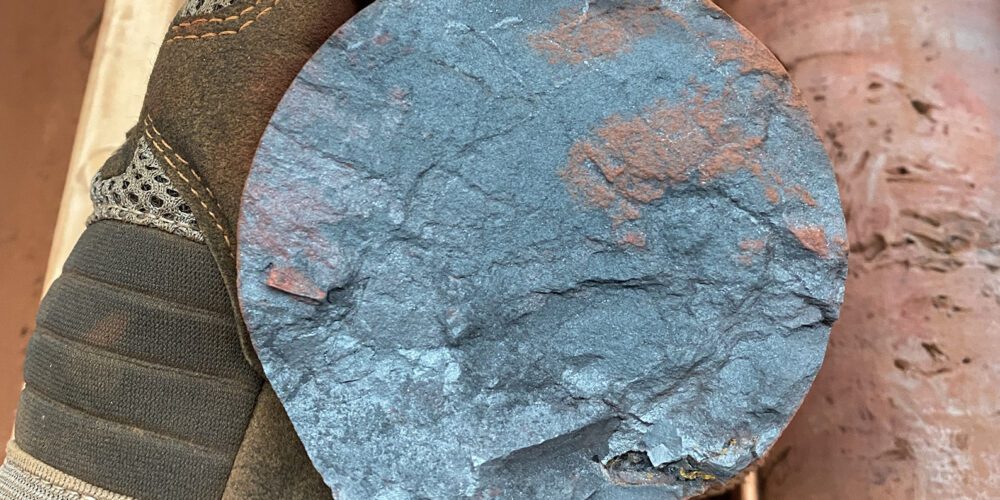

Study co-author Associate Professor Martin Danišík, from the John de Laeter Centre, said the research precisely dated minerals from banded iron formations (BIFs), which are ancient underwater layers of iron-rich rock that can provide significant insights into the Earth’s deep geologic past.

“Until now, the exact timeline of these formations changing from 30 per cent iron as they originally were, to more than 60 per cent iron as they are today, was unclear, which has hindered our understanding of the processes that led to the formation of the world’s largest ore deposits,” Associate Professor Danišík said.

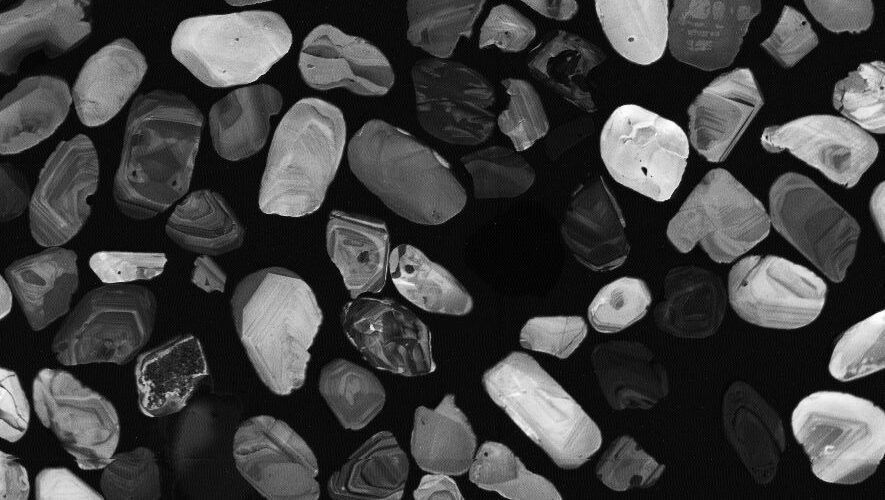

“By using an emerging technique to date iron oxide minerals through uranium and lead isotope analysis within the mineral grains, we directly dated all the major giant BIF-hosted iron ore deposits in the Hamersley Province.

“Our research indicates these deposits formed in conjunction with major tectonic events, highlighting the dynamic nature of our planet’s history and the complexity of iron ore mineralisation.”

Western Australia is the world’s leading producer of iron ore, which is Australia’s largest export earner at $131 billion last financial year.

The research was done in collaboration with researchers from The University of Western Australia, Rio Tinto and CSIRO Mineral Resources.

The study is a contribution to the “MRIWA 557” project supported by Bureau Veritas, BHP, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Fortescue Mining Group (FMG), Rio Tinto, Roy Hill, and Minerals Research Institute of Western Australia (MRIWA) and by the Australian Research Council through the Centre of Excellence for Core to Crust Fluid Systems (CE1100001017). Research in the GeoHistory Facility was enabled by AuScope (auscope.org.au) and the Australian Government via the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy.

The full study titled ‘A Billion-Year Shift in the Formation of Earth’s Largest Ore Deposits’ will be published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal (PNAS) and once published can be found here: https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2405741121