Mining digs into the circular economy

After the Western Australian government announced in June that it would start ‘decarbonising’ the state, the mining industry and science research teams began preparing for some groundbreaking collaborations.

At Curtin, Professor Michael Hitch is leading the first step of the process: the drafting of the ‘decarbonisation roadmap’, which he intends to align with models of ‘the circular economy’.

Hitch, who heads the Curtin WA School of Mines: Minerals, Energy and Chemical Engineering, believes in the resources sector’s ability and motivation to set new standards in the circular production model of reduce-reuse-recycle.

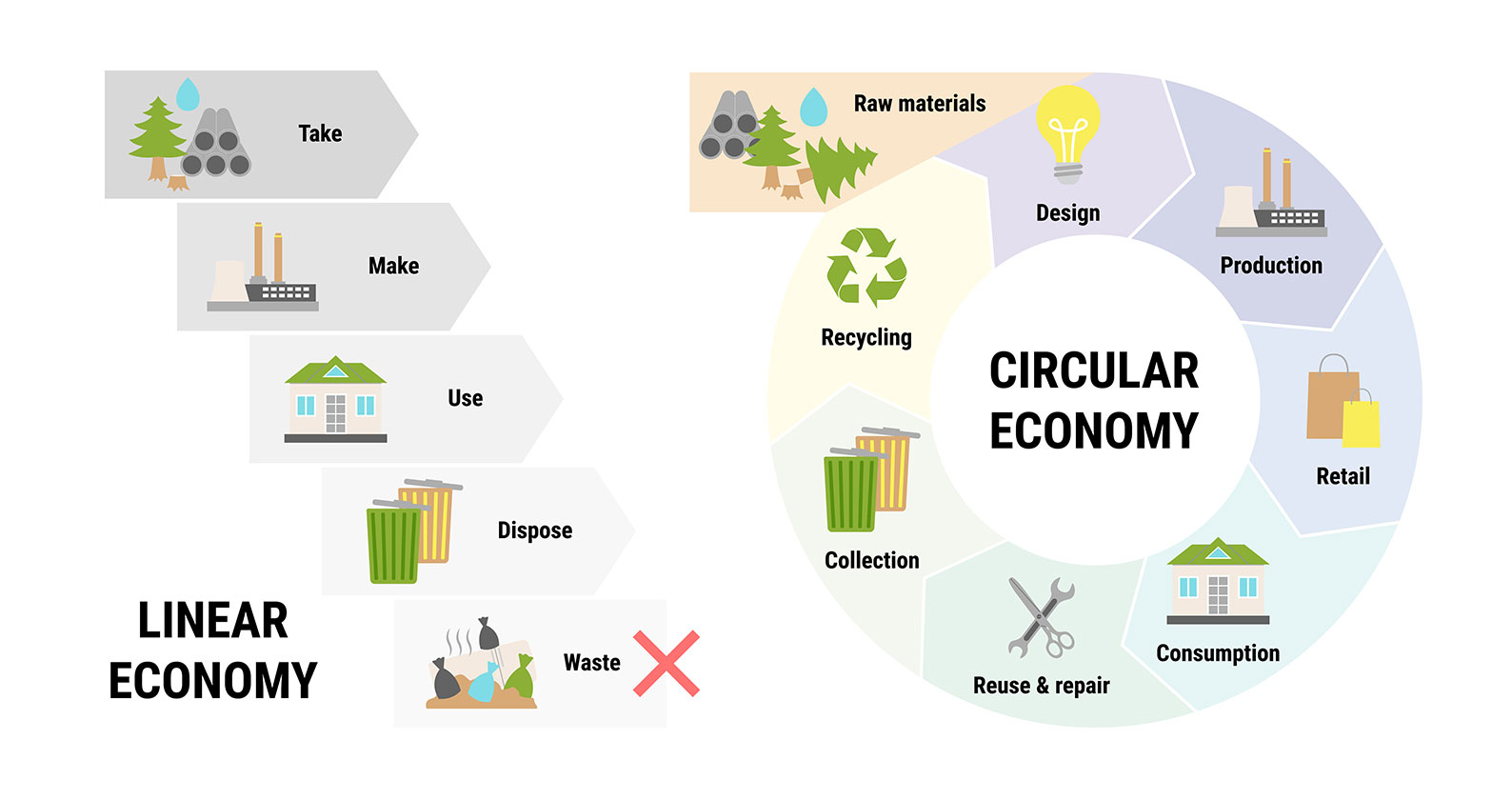

“It’s a critical alternative to the linear model we’re accustomed to, which is to produce, then use, then dispose,” he explains.

“In the circular model, we produce, we use, but we never really dispose. Or we do it in such a way that the manufactured goods can be disaggregated and returned to the production stream.”

For a mining company, supporting a circular model involves minimising the impact of mining operations on the land, converting mining waste into useful by-products, and undertaking land rehabilitation once mining ceases. And it’s the waste from mineral extraction that’s driving the industry’s entry into the circular economy.

“In mining – and in the resources sector in general – we produce a lot of waste. We call it ‘waste’ but really it’s just broken rock, which is either put it into dumps or tailings ponds. In the circular model, we aim to up-value that waste to the point of creating a viable byproduct.”

“The circular mode is usually quite static, with little room for economic growth. However, up-valuing waste can actually help to grow an economy, and occasionally we might even develop by-products that are worth more than the materials generating that waste”.

‘Metals leasing’ is another bold concept that Hitch believes has merit.

“Basically, it’s blockchain and supply-chain management, tracking that ton of ore through its life cycle. The person who’s using the steel to manufacture a product isn’t buying it, they’re leasing it, within a circular economy. When the product is at end-of-life, it can return to the manufacturer or the miner as a recyclable.”

What do artificial reefs, blueberries and paint have in common?

The development of viable by-products from mining and smelting is fast becoming a global research movement. At its core is the commitment of all 27 members of the International Council on Mining and Metals to a goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Some companies have already implemented initiatives to achieve the goal; Novum Energy, BHP and Anglo American, for example, are recycling discarded dump-truck tyres into oils and steel. And Rio Tinto, which is aiming for a 50% emissions reduction by 2030 – a mere eight years from now – is developing blueberry fertiliser from waste aluminium.

One of Hitch’s research focuses has been the potential for the mining by-product selenium to be a fertiliser enhancer. He’s also contributed to research looking at carbonated steel slag to create artificial reefs. But the area he’s most enthusiastic about is carbon capture and sequestration (CCS).

“Right now, BHP are investigating uses for their tailings, which is the material that’s left once the target mineral is extracted. In nickel mining, the tailings are effectively sand and they’re chemically neutral. But when in contact with carbon dioxide, the sandy material is reactive and the sand particle changes to a carbonate,” he explains.

“Because the carbonate is thermodynamically stable for about 100,000 years, it gives sand tailings the potential as a carbon capture and storage material. This would qualify the process for carbon offset credits.

He says the material could also form the basis on new industrial products such as building materials, animal feed, food fillers or paint thickeners. In fact, this year alone, Hitch as co-authored three research papers that explore the potential of tailings and steel slag to be the basis of new building materials.

“So there are at least three major benefits that nickel tailings offer: sequestering CO2, generating carbon credits, and forming a base for innovative industrial products. It’s a perfect example of circularity, where the waste has economic value, environmental value and social value.”

Don’t forget your social licence

Hitch joined Curtin in 2020, following 20 years’ industry experience, beginning as a field geologist and transitioning to mining operations and eventually to research.

“I’ve travelled a lot since my career began in the mid-80s and I’ve seen the good, the bad and the ugly of what mining can do,” he says.

He stresses that community acceptance of a company’s operations is vital for the industry’s future, and that mining companies must gain and uphold their “social licence to operate”, a concept that was the basis of a journal paper Hitch co-authored in 2021.

“The social licence to operate, or SLO, is about a trust that’s built between a mining company, or any industrial proponent, for that matter – it could be a shoe factory. It’s about bringing the community into the planning process and the operations, and being truthful in communication and transparent in operation – including when something goes wrong.”

“It must comprise community engagement, including what should be done to the land after mining operations cease, and a clear commitment to regulations.”

He says the concept of a social licence often is still missing in developing countries, where mining companies pay taxes and royalties directly to corrupt governments and where none of the mining wealth is distributed to local communities. Canada, and Australia to a lesser extent, have some of the highest environmental standards in the world.

“Canadian mining companies operating overseas to work, they’re held by the standards of Canadian law and policy. So if they go in and behave badly, they’ll be held accountable against Canadian standards. A few years ago, for example, Barrick Gold’s operations in Chile were stopped by the Canadian government, due to concerns about the impact on local water supplies.”

And, here in Australia, who could forget the unforgiveable blasting of the Juukan Gorge that’s still stigmatising Rio Tinto?

“Actually, the ‘big end of town’, as it’s known here in WA, is doing a really good job,” Hitch says. “They’re establishing programs and have specialists focused on sustainability and social responsibility, so that the local communities are not negatively impacted and preferably benefit from the operation.”

What does sustainability even mean?

Underpinning the circular model is the acceptance that, despite the mining industry’s titanic contribution to CO2 emissions, mining will remain integral to most economies for the foreseeable future. That isn’t due only to the enduring demand for products that use traditional mineral resources for construction materials, but also to the rising need for critical minerals that underpin modern gadgets and technological innovation.

But with the growing call to adopt more sustainable practices, what will mining operations look like in the future?

“Sustainability as a term has become a bit diffused,” Hitch says. “We think of ‘sustainability’ as being able to continue doing what we’re doing without sacrificing the needs of future generations. But there’s another part to it that many people don’t want to acknowledge – and that’s if it’s feasible.”

Recalling a mining conference at which Indian prime minister Narendra Modi revealed that 40% of India’s population lived without electricity, Hitch believes the challenges faced by developing nations deserve greater attention.

“Fortunately for WA, we produce most of the material that will be required for the infrastructure of the future – iron ore and specialty metals like nickel and lithium. But we also have a wealth of mining technology and knowledge, and we should export this knowledge to help lift nations out of poverty, help smooth their energy transition and minimise environmental impact,” he explains.

“But we have to come up with alternative models of the materials that we are producing. Sustainable resource use is about mining to meet need, not mining that’s economically valuable due to market conditions.

“Ideally, we’d be able to estimate how much steel the world will need for the next 25 years, then and develop mines that will provide the iron ore to produce the steel for the next 25 years. It’s ‘material stewardship’”.

Mining becomes part of the solution

As part of WA’s decarbonisation plan and with support from the Minerals Research Institute of Western Australia, Hitch will develop a research program that offers exciting collaborations for the state’s mining industry.

For example, one project aims to develop methods that accelerate the natural process of mineral carbonation, a natural rock weathering process where CO2 binds to minerals in the Earth’s crust, thereby removing CO2 from the atmosphere, albeit slowly. The project builds on one of Hitch’s recent international collaborations that investigated sequestration processes for commercialisation, based on the potential for mineral carbonation to provide greater storage capacity than other CCS methods, such as geological and ocean sequestration.

“Again, nickel tailings are ideally suited for this purpose, and we’re working with BHP Nickel West on methods to increase the carbonation reaction to store CO2 into its tailings.”

If successful, the project’s outcome will be a new solution for large-scale storage of CO2 emissions, at the gigatonne scale. And with WA holding about 30% of the world’s nickel reserves, and nickel being highly sought after for electric vehicle batteries, Hitch says that “WA could sequester more emissions than we produce – and set a new level of mining industry innovation”.

“At the end of the day, it’s about resource utilisation and stewardship. If we’re going to dig into the land, we should find ways to extract value from everything that we take out of the ground, including the waste material that didn’t previously have economic value.”