Buy now, pay later: the new black or a deep black hole?

If video killed the radio star, ‘buy now, pay later’ services may be the death of credit cards. But before you cut up your plastic, it’s worth knowing the appeal and pitfalls of these ‘instant gratification’ schemes.

“These services can benefit you if you are disciplined, but if you overindulge and can’t afford to pay the late fees, that’s when problems arise,” says Professor Saurav Dutta.

Professor Dutta has been critiquing buy now, pay later (BNPL) services with Dr Lien Duong, a Senior Lecturer in the School of Accounting, Economics and Finance, as part of their research practice. He says that while credit card use in Australia has plateaued, BNPL has surged in popularity, especially since the pandemic hit Australia in March 2020 (in fact, Afterpay’s share price skyrocketed from A$8.90 on 23 March 2020 to A$75 on 21 July 2020).

“Their rising popularity has to do with technology making electronic payments easier and more secure, more online shopping, increasing distrust of banks and younger people shying away from credit card use.”

How it works

BNPL lets you purchase something instantly and pay for it later in instalments. Unlike other repayment schemes, these services don’t charge interest on what you owe, only a late fee if you don’t make repayments on time. Some providers, like Zip Co, charge a monthly flat rate on whatever is owed.

Unlike applying for a credit card, which takes time to approve and requires a credit check, all you need to open a BNPL account is to be over 18 years of age and have a debit or credit card. Some providers do perform credit checks, but many approve accounts almost instantly.

Fintech’s rising star

The convenience of BNPL has seen the fintech sector hail it as the ‘next Uber’. Between them, BNPL giants Afterpay and Zip Co have more than five million active Australian customers. A report released in November 2020 by the Australian Securities Investments Commission (ASIC), revealed BNPL transactions in Australia increased from 1.9 million in June 2018 to 3.4 million in June 2019 – a jump of 75%. The report also revealed that the total value of all transactions increased by 79%, from A$3.1 billion in the 2018 financial year to A$5.6 billion in the 2019 financial year.

Professor Dutta says the psychological appeal of BNPL lies in ‘rational expectation’.

“It enables consumers to buy something they otherwise couldn’t afford, based on the expectation that they will be able to afford it at a later date.”

Dr Duong adds that this type of spending appeals to millennials in particular. “They may have lower salaries, but they’re more likely to make impulse purchases,” she explains.

ASIC estimated that 47% of BNPL users surveyed were aged 18 to 29, and two in five had an annual income below A$40,000.

Buy now, regret later

BNPL may offer instant gratification, but it’s this very factor that leads some consumers to financially over-commit and accumulate hefty late fees.

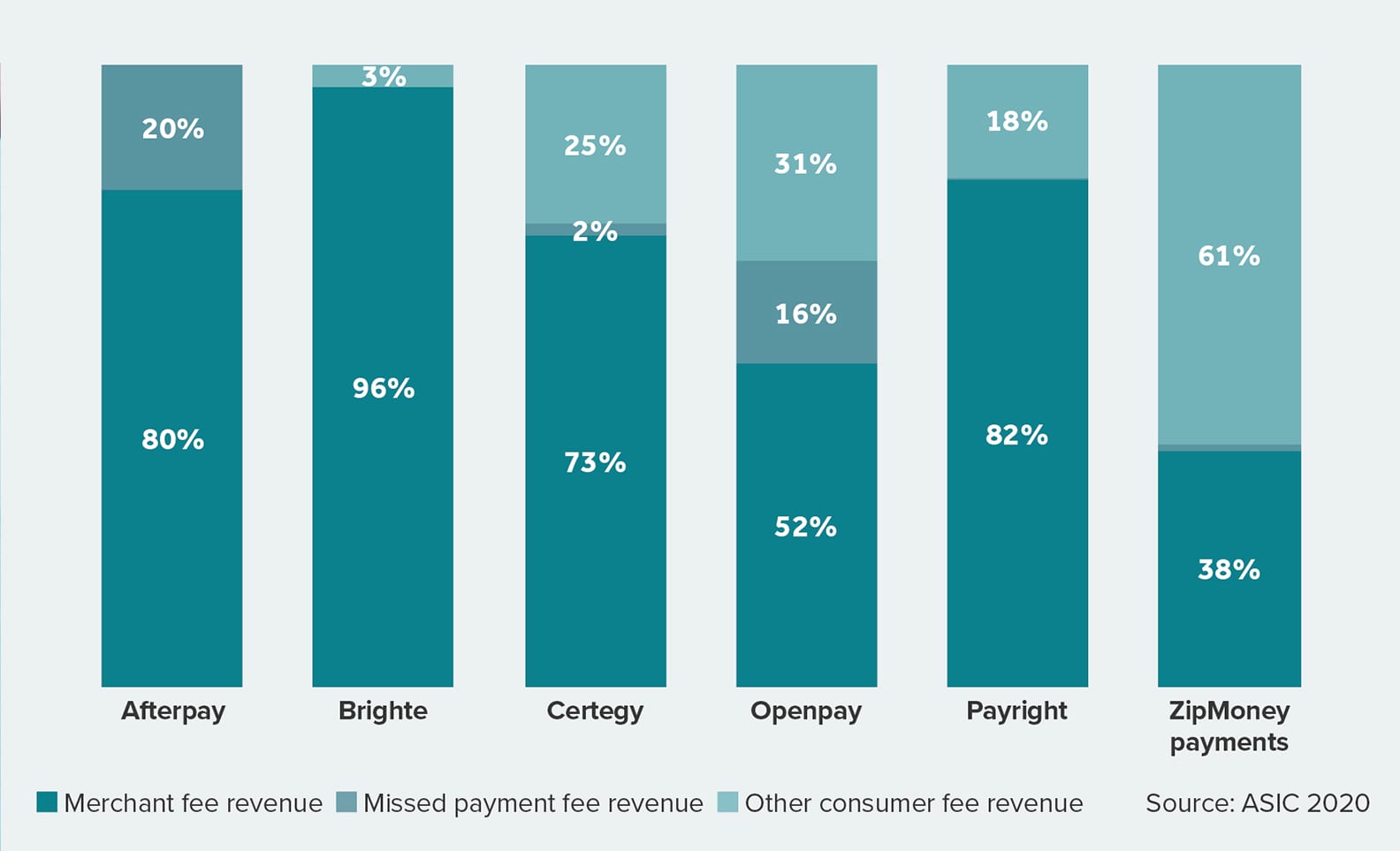

ASIC found that missed payment revenue totalled A$43 million for six major BNPL providers for the 2018–19 financial year. At 20%, late fees make up a larger portion of Afterpay’s revenue than its competitors.

“If you miss a repayment to Afterpay, you will be charged $10, and another $7 if the payment remains unpaid seven days after the due date,” Professor Dutta explains.

“So late fees could really add up. On a debt of A$150, just one A$10 late fee translates to an effective interest charge 6.67% for the fortnight. Just consider what a couple of late fees would equal in terms of an annual interest rate.”

These late fees are causing significant financial stress for some Australians. ASIC found that 21% of BNPL consumers surveyed missed a payment in the 12 months from October 2018–2019.

One in five had also missed or delayed paying other bills, like credit card payments and mortgages, in order to make their BNPL payments on time.

The fight to tighten loopholes

The reason BNPL companies can seemingly lend money to people who may be least likely to make timely repayments comes down to the fact that they’re not actually credit providers.

“The ‘quasi-interest’ these companies charge in late fees does not technically count as interest, so BNPL providers are not covered by the National Credit Act, and therefore aren’t required to observe the Act’s responsible lending obligations,” explains Dr Duong.

Professor Dutta and Dr Duong have been waving red flags about these loopholes for some years now, and people are taking notice. In 2019 they published an article in The Conversation about Afterpay’s late fees. It garnered 15,000 readers on its first day of publication and was subsequently re-published in The Guardian and other online news outlets.

In January 2020, Professor Dutta, Dr Duong and two colleagues submitted a review of BNPL to the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). It detailed several ways the RBA could coordinate regulatory and industry action on BNPL providers to better protect consumers and merchants.

ASIC concluded in its 2020 report that ‘design and distribution obligations will apply to … buy now pay later arrangements.’ In part, this means BNPL providers must be fully transparent about the services they offer, and for whom they are most appropriate.

The RBA and ASIC stopped short of recommending that BNPL providers be regulated in the same way that credit card companies are, but consumers are at least more aware of what they’re signing up for.

“BNPL is not a bad service, and if someone I knew wanted to use it, I would say do so, but know your limits,” advises Professor Dutta.

“If you’re not an impulse buyer, it can be a good platform for you,” adds Dr Duong. “But basically, it comes down to financial literacy: if you don’t have the money, don’t buy it.”

Researcher profiles

Dr Lien Duong is a Senior Lecturer in Curtin’s School of Accounting, Economics and Finance. She has worked in the accounting and finance industry as a management accountant, tax accountant and business analyst. Her research has been published in international journals and focuses on mergers and acquisitions, merger waves, executive compensation, corporate governance, financial reporting quality and statistical modelling.

Professor Saurav Dutta was Head of Curtin’s School of Accounting from 2017 to 2020. Throughout his 25-year academic career, he has engaged in high-impact research that has informed industry practice and public policy, including the Wall Street reforms in the US following the 2008 global financial crisis. He has since moved to the US, where he is continuing his academic career.